Blog

The Metrics Game: When Toxic Leadership Comes Full Circle

By Jay

Series: Leadership

Tags: systems-thinking, technical-management, observability, organizational-behavior, leadership

There’s a particular breed of toxic leader that seems to thrive in operations departments. These leaders mistake authority for leadership and confuse control for competence. From the top down, they give the appearance of success because they control the narrative for their groups, supported by charts full of quantifiable data showing how great they’re doing.

Operations groups are particularly susceptible to this type of leader because they encompass some of the most measurable aspects of IT: infrastructure operations, support functions, and data center buildouts. SLA adherence, mean time to resolution for support tickets, infrastructure capacity and performance, construction timelines, equipment deployment schedules—these numbers are readily accessible and seemingly objective. While other IT functions certainly have quantifiable metrics, they’re often more complex or require deeper context to interpret meaningfully. In my career, operations is where I’ve consistently encountered these metrics-obsessed leaders, though it’s only recently that I’ve started seeing similar dynamics creep into development teams with the rise of DORA metrics and other developer productivity measurements.

The appeal of operations metrics is obvious: they look authoritative and scientific, providing a veneer of data-driven decision-making that’s easy to present to executives who may not understand the underlying complexity. But appearances can be deceiving. The further removed these metrics become from actual operational reality, the less meaningful they become, and the faster that facade crumbles. Leaving the leader exposed.

The Interrogator’s Playbook

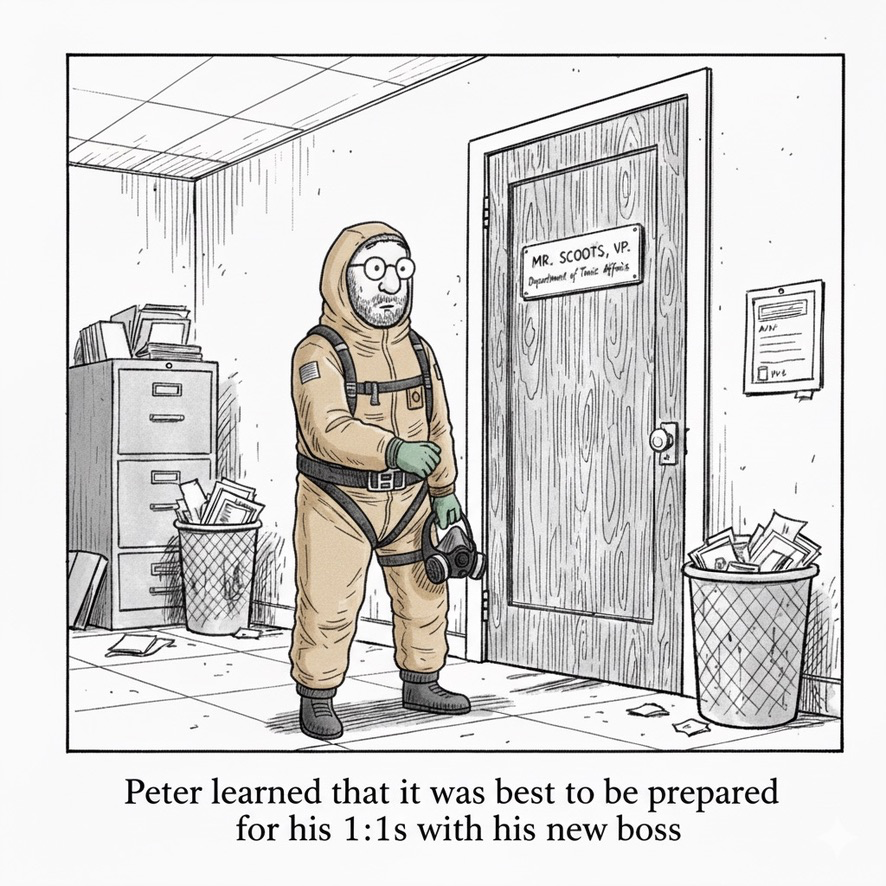

These metrics-obsessed leaders typically employ a characteristic management style: every conversation becomes an interrogation. Team members asking questions about process or policy get grilled about why they need to know. Those raising concerns about systems or customer issues must justify why their concerns are worth leadership’s time. This approach creates a pervasive atmosphere of suspicion, even when people are trying to help.

In my case, the operations VP I worked under had perfected this art. He was an ex-cop who ran his department like an interrogation room and treated his people like spreadsheet entries. He made sure everyone knew he was in charge, and that questioning him was not an option. This created a death of initiative in the groups that reported to him. People stopped bringing up problems or suggesting improvements because nobody wanted to get yelled at for real or perceived failures, regardless of how much the company needed those insights.

Perhaps most telling is these leaders’ strange pride in not knowing operational details. They typically have a system that worked at another company, and that gives them all the knowledge they think they need. Unlike effective leaders who work to understand their environment, customers, and industry context, they breeze past those concerns and execute their single playbook.

In my experience, this VP’s way became the only way within days of his arrival. To provide one example, he insisted on using Excel for all reporting, despite the fact that our entire organization used Google Workspace. Why? Because, in his words, “Excel is the only way to track changes.”

Everyone was forced to create spreadsheet after spreadsheet full of what he deemed key performance indicators, email them as attachments (he also had issues with Google Drive), wait for updated versions to be emailed back, then repeat the process. In his words, he was “making things more efficient.” In reality, this was intellectual laziness disguised as executive decision-making, all given legitimacy by fabricated charts and graphs, backed by a personality that few people wanted to challenge.

Another bit of ludicrousness was one of his managers insisting that the Network Operations Team (NOC) take screenshots of the key metrics dashboards every hour and email them to him. This is despite the fact that the NOC was using the monitoring system this manager had selected and signed a contract for, a monitoring system that allowed for historical trending and reporting. When asked why they were doing this, the manager exploded and told his team “this is not a discussion” and slammed his desk.

The Loyalty Test

What makes this leadership style particularly toxic is how it cascades through the organization. Direct reports quickly learn that success means adopting the leader’s approach: condescending interrogations, dismissive attitudes toward subordinates, and an obsession with metrics divorced from meaning. Those who can’t or won’t adapt find themselves marginalized, transferred, or pushed out entirely.

The loyalty test is simple: will you treat others the way the leader treats you? If yes, you’re management material. If no, you’re a problem to be solved. The result is a culture where respect is scarce, and fear is abundant. Essentially, these leaders create mini-versions of themselves throughout the organization, perpetuating the cycle of toxic behavior. A sort of rehash of the Stanford Prison experiment, but with more spreadsheets.

During layoffs, this dynamic reaches its most dehumanizing point. Leadership teams often can’t be bothered to remember the names of the people they’re eliminating. While layoffs are common in the tech industry and can be conducted in a human-first way—treating people like colleagues with families, mortgages, and careers—in these environments, emotional investment in people is seen as weakness. One of my VP’s lieutenants walked into a meeting after laying off several employees and couldn’t remember their names literally five minutes after firing them (nor did he care). Perhaps not shockingly, this was treated as a badge of honor, a sign of strength and detachment.

The Deflection Strategy

Perhaps most frustrating is these leaders’ approach to accountability. When faced with actual work or ownership of outcomes, their first response is always the same: find another group to pawn the task off on.

I experienced this firsthand when trying to transition my responsibilities to the newly hired Director of Operations. Training? That’s the training department’s job. On-site engagement? That belongs to professional services. Writing up customer issues? Obviously that’s the product team’s responsibility. The fact that none of those groups existed wasn’t considered relevant. These were things the company needed, but the only concern was absolving the operations group of any responsibility.

This deflection isn’t just about avoiding work. It’s another facet of maintaining the illusion of control. By never owning a problem, these leaders never have to own a solution, which means they never have to demonstrate actual competence beyond their ability to interrogate and intimidate over a finite set of metrics.

When the Tables Turn

The beautiful irony comes when corporate oversight turns their way and begins questioning why, despite all the glowing numbers, long-term commitments aren’t being met. Suddenly, these leaders experience their own treatment: interrogation about numbers without context, dismissal when trying to explain operational nuances, and watching decisions made by people who proudly don’t understand the details.

I’ve been on the receiving end of this kind of executive scrutiny myself. I once had a CEO practically scream at me about a graph that was, and I quote, “going the wrong way,” demanding to know why. It took fifteen minutes to explain that I had no idea what graph he was talking about or what it was measuring. He admitted he didn’t know what it measured either, only that “up was bad.”

In my case, when our corporate parent (we called them the Eye of Sauron) turned their attention to our VP, the transformation was remarkable. The man who had spent his entire tenure conditioning people to accept disrespectful treatment couldn’t handle a fraction of his own medicine. He went from confident interrogator to whining victim faster than you could say “management restructure.” His normal deflection strategy no longer worked, and I found myself in numerous meetings where he spent most of the time blaming the parent company for issues directly impacting our work with zero admission of his own role in creating those problems.

The Exit Strategy

The final chapter for these leaders follows predictable patterns, though the specific details vary. Some quit before they can be fired, others get quietly moved to “special projects,” a corporate code for a face-saving transition period before they’re allowed to resign. Some negotiate severance packages that let everyone pretend it was mutual, while others simply fade away into lateral moves within larger organizations where their reputation hasn’t preceded them.

In my VP’s case, the ending was particularly dramatic: a rage-quit followed by a lengthy Glassdoor rant about how unfairly he’d been treated. The same person who had pushed dozens of good people out of the organization was now complaining about toxic leadership and lack of respect from above. Reading that post was like watching someone discover empathy for the first time—except it was entirely self-directed. There was no recognition of the irony, no acknowledgment of the culture he’d created, no understanding that he was experiencing exactly what he had put others through for years.

But regardless of whether they rage-quit with public complaints, quietly slink away to “special projects,” or negotiate their way out with golden parachutes, the pattern remains consistent: these leaders who built their careers on breaking others down rarely handle it gracefully when the treatment flows uphill.

Breaking the Cycle

The good news is that this style of leadership is increasingly recognized as ineffective. Organizations are starting to understand that sustainable results come from engaged, empowered teams, not intimidated ones. The metrics-without-meaning approach is being replaced by data-driven decision-making that actually considers context and nuance.

But we still need to be vigilant. When you see a leader who takes pride in not knowing details, who treats every interaction like an interrogation, who builds loyalty through intimidation rather than inspiration, recognize the pattern. Call it out when you can, protect your team when possible, and remember that their eventual downfall is often just a matter of time.

After all, leaders who rise by treating people poorly rarely handle it well when the treatment flows uphill.

This connects to broader themes about leadership, organizational culture, and the importance of treating people as humans rather than resources. For more thoughts on leadership challenges and team dynamics, check out my posts on leaders who fail up and the normalization of deviance.