Blog

Building World-Class Support: Commandos, Not Armies or MPs

By Jay

Tags: support, leadership, team-building, organizational-culture, customer-service

Late on a Friday afternoon, a customer’s authorization token expired. Their entire infrastructure started failing, one cluster at a time. They submitted a ticket. Support’s response: a canned macro and a closed ticket. The customer was still down. As far as support was concerned, they were done.

This is when I learned the difference between support that follows procedures and support that solves problems.

The customer relied on our product as a core component of their infrastructure. My company didn’t offer phone support, so they’d submitted a ticket via the ticketing system. The account executive had to push the support team to even look at it. Support kept noting that their SLA was 24 hours and they had other things they were working on. When they finally got to it, they used a macro and closed the ticket without solving anything.

This is where I got involved. The AE and I were friends, so he called me in frustration. “They’re not helping the customer! What do I do?”

At this point I was working as a solutions engineer (SE), not in support. SEs typically help with pre-sales technical questions, demos, and proof-of-concepts. We don’t do support. But I could see the customer was in trouble and support was failing them, and having been in their shoes before, I felt compelled to help.

I worked directly with the customer to diagnose the problem and developed a workaround to keep things running. Then I escalated to the CEO for approval to make a temporary account change that would unblock them. Why the CEO? Because the support organization was still studiously ignoring the customer’s needs.

The AE was satisfied. I was furious. Although we had solved the customer’s problem, I was deeply unhappy with how the support organization had handled it. A customer’s production infrastructure was down for hours because support refused to engage during business hours. An AE had to bypass our support team to get help. And I had to step in to do support’s job.

The internal result of that experience? A righteously indignant support team that felt the SE team (well, me) had not “permitted them to do their job.”

That’s when it crystallized for me: our support organization was a collection of Military Police with a leader who liked it that way and would fight to keep it that way.

The Framework

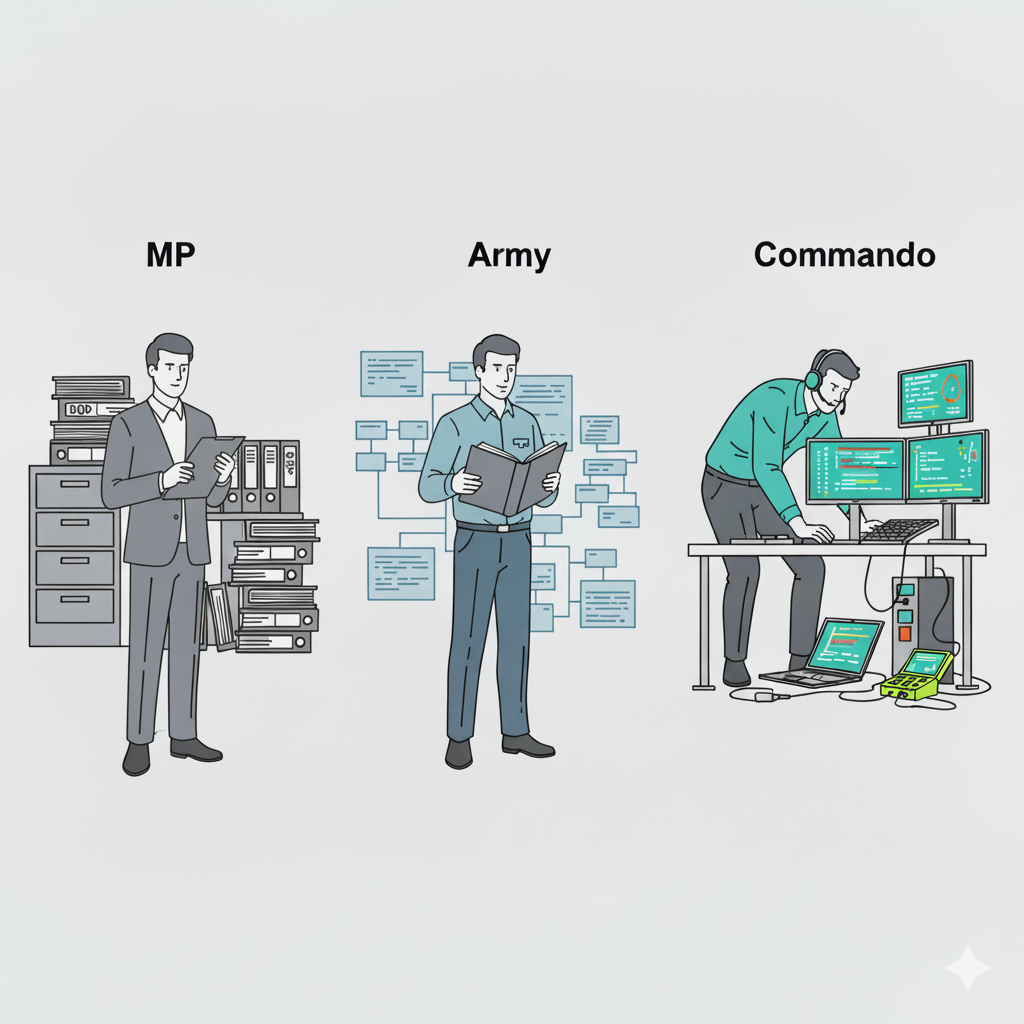

This way of thinking about organizational roles comes from Robert X. Cringely’s Accidental Empires, where he uses Commandos, Infantry, and Military Police as a framework for understanding how companies evolve. Commandos storm the beach and establish the beachhead. Infantry come behind them to build the fortifications and hold the territory. Military Police arrive last to enforce order and maintain what’s been built.

Cringely was describing company lifecycle; the natural progression from startup chaos to enterprise structure. But I’ve realized this framework applies just as powerfully to how support organizations operate, with one critical difference. Unlike companies that naturally evolve through these phases, support teams need to resist that evolution. The best support organizations find ways to preserve commando culture even as they scale.

The Three Types: How They Solve Problems

Every support organization I’ve encountered falls into one of these three categories. The differences become immediately obvious when you watch them handle the same problem.

Let’s start with a common scenario: A customer submits a ticket saying “Data isn’t syncing between systems.” Not an emergency, but it’s blocking their work. Here’s how each type of organization handles it.

The MP Response: Following the Script

The ticket lands in the queue. An MP picks it up and checks the time (still within SLA) before opening the knowledge base. They find an article titled “Data Sync Issues” that says to check if the customer has the latest version. They send a canned response: “Please verify you’re running version 2.4 or later and let us know if the issue persists.”

The customer responds: “I’m on 2.4.1 and it’s still not working.”

The MP checks the knowledge base again and finds nothing else. They escalate: “Escalating to engineering as issue persists after basic troubleshooting.” Ticket closed on their end. Time to first response: 45 minutes. Time to resolution: TBD.

The MP’s metrics look great. They followed procedure. But the customer’s problem? Still not solved.

When MPs Work

MPs work when the problem is well-defined, the solution is documented, and volume matters more than creativity. Password resets. Account unlocks. “Where do I find X in the UI?” These are legitimate support needs, and an MP can handle hundreds per day efficiently.

The problem isn’t that MPs exist. It’s when they’re the only model, or when they’re applied to problems that require stepping outside their scripts, checklists, macros, and knowledge base articles. That’s when you get the pattern I described earlier: close the ticket without solving the problem because it’s easier than admitting you don’t know the answer.

This is where it gets dangerous: the MP model doesn’t start broken. It starts with reasonable people making reasonable compromises. A team has a policy that every issue gets solved, not just closed. But one day they’re swamped. Someone suggests, “Just close this one, the customer stopped responding anyway.” The next time, it’s easier. Before long, closing tickets without solving problems becomes the norm as long as the customer doesn’t complain.

We have a phrase for this: “normalization of deviance”. What starts as a one-time exception becomes standard operating procedure. The deviation stops feeling like a deviation at all. This is how you end up with teams that studiously ignore customer needs while hitting all their SLA metrics.

The Army Response: Executing the Playbook

The ticket is routed to a specialist who has seen data sync issues before. They have a documented troubleshooting process: check version, verify API keys, confirm network connectivity, review sync logs, check for known bugs in the release notes.

They work through each step methodically and ask the customer for log files and configuration details. They identify that the customer’s API rate limit is being exceeded during peak hours. They know the fix: adjust the sync frequency in the configuration file. They provide clear instructions. The customer implements them and reports that things look better. Ticket closed.

Time to resolution: 4 hours. The playbook was followed correctly. The reported symptom was addressed. The customer seemed satisfied.

When Armies Work

The army model shines when you have predictable complex problems that benefit from documented processes. A known outage affecting multiple customers? The army executes the incident response playbook flawlessly. A compliance audit requiring detailed documentation of every customer interaction? The army’s structure is exactly what you need. Multi-step onboarding processes that must be followed consistently? Army territory.

Armies are also good at coordinated responses at scale. When you need five people working together on a complex migration, following a detailed runbook, the army’s clear roles and communication protocols prevent chaos. They can handle sophisticated issues as long as those issues have been seen before and the solution is documented.

The limitation is predictability. When something novel happens and the playbook doesn’t have an answer the army grinds to a halt. “Let me check with my manager.” “That’s not in our scope.” “I’ll need to file an enhancement request.”

I’ve seen this pattern repeatedly. A customer has a problem that doesn’t fit the documented procedures. The ticket languishes in the queue or gets picked up by someone who tries to force-fit a playbook solution that doesn’t actually work. Eventually it gets escalated to engineering, then to product, then to executives. Information gets lost in translation with each handoff. Context evaporates. The customer explains their problem three times to three different people.

The army model works great when there’s a clear path to hand off novel problems to the right specialized team. But if the organization doesn’t have those communication channels, bad things happen. The catch: the army’s greatest strength—scalability—is also its weakness. When you add capacity, you almost always add layers of management and process. This reduces agility and makes it even harder to respond to those unique problems.

The Commando Response: Owning the Outcome

A commando sees the same ticket and immediately wonders: what kind of data, what systems, when did it start? They pull up the customer’s account and check the sync logs directly. They spot something odd: successful API calls, but the data isn’t appearing in the destination system.

This isn’t a rate limit issue at all. This is a data transformation problem—one that slowing down the sync frequency might mask temporarily but won’t actually fix.

They reproduce it locally using the customer’s data format. They find a bug introduced in the last release that fails silently when processing certain date formats. They file a bug report with engineering and provide a complete reproduction case. Within an hour, engineering has a fix ready.

But the customer is blocked now. The commando writes a quick script to transform the customer’s data into a format that works with the current version. They run it for this customer and sync the backlog. Then they schedule a call to walk the customer through the workaround until the fix is deployed.

Time to resolution: 2 hours. The actual problem identified and fixed. Bug documented. Customer unblocked with a workaround. And when the customer with the “rate limit issue” contacts support again next week because slowing down the sync didn’t really solve their problem? The commando’s bug fix will already be deployed.

When Commandos Work

Commandos are built for everything the other models can’t handle. Novel problems that don’t fit any playbook? Complex multi-system issues that require end-to-end understanding? High-stakes emergencies where every minute counts? Root cause investigation that prevents the problem from happening again? That’s commando territory.

Remember that token expiration issue from the beginning? Here’s how a commando would have handled it differently. They see the ticket come in: “Authorization token expired, infrastructure failing cluster by cluster.” They don’t check the SLA. They don’t look for a macro. They immediately recognize this is critical—a customer’s production infrastructure is actively failing.

They pull up the customer’s account and see the expired token. Within minutes they generate a new one and send it to the customer. But they don’t stop there. They check why the token expired without warning and find a gap in the renewal notification system. They file a bug report with reproduction steps. Then they follow up with the customer to ensure everything is back online and document the incident for the retrospective.

Total time: under an hour. No escalations to the CEO. No bypassing support through the AE. Just someone with the skills, authority, and judgment to solve the problem completely.

Commandos punch way above their weight class. A team of five exceptional people can outperform 50 mediocre ones. Lower communication overhead. Faster decisions. No hand-offs where context gets lost or responsibility gets diffused.

What separates good commandos from great ones: they don’t just solve the immediate problem. They prevent it from happening again. They participate in retrospectives. They update documentation. They improve processes. They identify patterns across customer issues and work with engineering to address root causes. They don’t just put out fires; they build firebreaks.

Why Commandos Win

The commando approach works because it aligns incentives correctly. When you give people the skills, authority, and trust to solve problems completely, remarkable things happen.

Technical Depth Changes Everything

Think about the difference between line cooks and chefs. Line cooks follow recipes perfectly. Chefs understand ingredients, techniques, and principles well enough to improvise when things go wrong.

Support commandos are chefs. They can read code. They understand system architecture. They’ve spent time in the database. They can write scripts to automate repetitive tasks. This isn’t because they’re trying to replace engineers. Rather, it’s because technical literacy transforms support from “reporting problems” to “solving problems.”

When a customer reports strange behavior, a line cook files a ticket. A chef digs into the logs and reproduces the issue locally. They identify the pattern and either fix it or provide engineering with a complete reproduction case that cuts debugging time by 80%.

Extreme Ownership Builds Trust

The best support interactions I’ve witnessed all share one characteristic: the customer never doubted who was responsible for making things right. No hand-offs. No transfers. No “let me get back to you.” Just one person saying “I’ve got this” and actually delivering.

This is the opposite of how most organizations operate. We love to talk about breaking down silos, but in practice we build rigid organizational boundaries that make it someone else’s problem. The ticket gets passed to engineering. Engineering kicks it to product. Product says it’s working as designed. Meanwhile, the customer is stuck in purgatory.

Commandos bypass all that nonsense. They own the outcome. If they need to pull in engineering they do, but they stay involved and accountable throughout. The customer has one point of contact who knows everything that’s happening.

This requires psychological safety. I’ve written before about Crew Resource Management—the safety framework born from disasters like United Airlines Flight 173. In that crash, the flight engineer knew they were running out of fuel. He mentioned it. Multiple times. But the captain was focused on troubleshooting a landing gear issue and didn’t respond to the warnings. The plane crashed, killing 10 people. The information needed to prevent the disaster was in the cockpit. The hierarchy prevented it from being heard.

Aviation learned from this. They developed CRM: a framework that makes it not just acceptable but mandatory for junior crew members to speak up, challenge decisions, and even override the captain in life-threatening situations. The copilot doesn’t need permission to say “We need to land now.” The flight engineer doesn’t need to couch their warnings in deferential language.

Support teams need the same framework. Your commandos need to be able to escalate issues, challenge decisions, and speak up when they see problems brewing—without fear of being labeled “not a team player” or “difficult to work with.” When a junior support engineer sees a pattern that indicates a critical bug, they shouldn’t need to get approval from three layers of management before filing a P0 ticket. When they recognize a customer issue is more urgent than the SLA suggests, they shouldn’t need permission to treat it as such.

Small Teams, Big Impact

There’s a reason special forces units are small. Beyond a certain size, communication overhead kills effectiveness. Every new person on the team is another person who needs context, another potential single point of failure if they don’t have the full picture.

I’d rather have five exceptional commandos than 50 people who need to check with their supervisor before making any decision. The math is simple: five people who can each solve 100 different types of problems give you coverage for those 100 problems. Fifty people who can each solve 10 types of problems give you… 50 bottlenecks when the 11th problem shows up.

How to Build Your Commando Team

Building an elite support team isn’t about hiring bodies to fill shifts. It’s about finding the right people and creating an environment where they can thrive.

Hire for Raw Talent, Train for Everything Else

Look for people with:

- Strong technical fundamentals (can they actually code?)

- Insatiable curiosity (do they dig deeper than required?)

- Customer empathy (do they genuinely want to help?)

- Low ego (will they ask for help when needed?)

I don’t care if they’ve worked in support before. I care if they have the mindset of someone who sees problems as puzzles to solve rather than tickets to close. Some of the best support engineers I’ve worked with came from QA, documentation, or even product management.

The technical skills you can teach. The attitude you can’t.

Give Them Real Power

This is where most organizations fail. They hire smart people and then handcuff them with approval processes and rigid boundaries.

Your support commandos should be able to:

- Access production systems (with appropriate safeguards and training)

- Expense hardware, software, and training required to replicate customer environments, recreate issues, and test fixes

- Make judgment calls about when to bend policies

- Deploy fixes to customer-specific issues

- Participate in product and engineering discussions

- Escalate as necessary to resolve customer issues

If your support team can’t do these things, they’re not commandos, they’re just expensive ticket routers.

Yes, this requires trust. Yes, there’s risk. But the alternative of slow, bureaucratic support that frustrates customers and demoralizes employees is riskier.

Measure What Actually Matters

Stop obsessing over time-to-first-response. Start measuring:

- Time to actual resolution (not ticket closure)

- Customer satisfaction scores (with written feedback)

- Number of problems solved at root cause

- Reduction in repeat issues

If your metrics incentivize closing tickets quickly rather than solving problems thoroughly, you’re building an army of MPs, not a team of commandos. And remember what I wrote about normalization of deviance: if you reward the wrong behaviors, they become the norm. “Just this once” becomes “just this always.”

Pay Them Like Engineers

Because they are engineers. Just with a customer-facing focus.

I see too many companies trying to hire “support engineers” at support salaries while expecting engineering-level skills. It doesn’t work. Underpay, and you get people who couldn’t make it as engineers. Pay competitively, and you get people who choose to work in support because they love the customer interaction and the variety of problems.

Your best support engineers could easily work as software engineers. They stay in support because they enjoy it and you pay them accordingly.

Avoiding the Traps

As you scale, there will be pressure to standardize and add processes and build the army. Some of this is inevitable. But you can resist the worst impulses.

Don’t Scale Too Early

I’ve seen this pattern repeatedly: company has 100 customers and two support people who are crushing it. Company grows to 500 customers and decides they need 10 support people to handle the volume.

Wrong.

What they actually need is to figure out why they’re generating so much support volume. Is the product confusing? Are there recurring bugs that need fixing? Are the docs inadequate?

Adding more support people scales the problem, not the solution. Keep your commando team small and use the leverage points they identify to reduce overall support burden.

Preserve the Culture Deliberately

As you add people, be ruthless about cultural fit. One person who treats support as “just a job” can poison the entire team. One person who views customers as annoyances rather than people with legitimate problems will drive your best people away.

Every new hire should spend time shadowing your best commandos. They should understand that the expectations are high and the autonomy comes with responsibility. If they want a job where they just follow a script, this isn’t it.

Beware Chesterton’s Fence

Things get dangerous when someone in leadership decides your commando team needs to be “professionalized.” They’ll want to add tiers and implement approval workflows. They’ll create escalation paths and standardize responses.

Before you do any of this, ask yourself: do I understand why the current system works?

I wrote about Chesterton’s Fence—the idea that you shouldn’t remove something until you understand why it was put there in the first place. Your commando team’s apparent lack of structure isn’t chaos. It’s optimized for speed and ownership. The “lack of process” is actually a deliberate design choice that enables rapid response and deep expertise.

When new leaders come in and try to impose traditional support structures they’re often tearing down the very things that made the team effective. They see a fence they think is unnecessary and remove it, only to discover too late that it was load-bearing.

Reddit learned this lesson the hard way when layoffs removed engineers with deep knowledge of legacy systems. When things broke there was no one left who truly understood how to fix them. The human infrastructure, the accumulated knowledge and experience, was the system, not an inefficiency to be optimized away.

Before you add structure, understand what you have and why it works.

Create Growth Paths

The biggest risk to your commando team is losing people because they see support as a dead end. Show them it’s not.

Some of your best product managers should come from support because they understand customer needs better than anyone. Some of your best engineers should come from support, since your average support engineer has debugged more production issues in a few months than most engineers see in years. Some of your best technical writers should come from support because they know what actually confuses people.

Make these transitions visible and celebrated. Let your team see that being a support commando is a launchpad, not a career cul-de-sac.

The Reality Check

Look, I’m not naive. You can’t run a 10,000-customer business with five support people, no matter how good they are. Eventually you’ll need some structure, some process, some specialization.

But you can maintain a core team of commandos who handle the hardest problems and mentor newer team members. They set the standard for what great support looks like. You can ensure that even as you add structure, you preserve the values that made your early support team special.

The goal isn’t to stay small forever. It’s to ensure that as you grow, you don’t lose what made you great in the first place.

The Test

You’ll know if you’ve built a commando team:

Ask your customers if they’ve ever been wowed by an interaction with support. Not satisfied—wowed. Not “my issue got resolved”—but “I can’t believe how much this person went above and beyond.”

If the answer is no, you don’t have commandos. You have order-takers.

If the answer is “occasionally,” you’re on the right track but not there yet.

If the answer is “regularly,” congratulations. You’ve built something special.

The difference between good support and great support isn’t about ticket volume or response times or staffing ratios. It’s about whether your team operates like MPs enforcing rules, soldiers following playbooks, or commandos completing missions.

Choose commandos. Your customers will thank you for it.