Blog

Printed on 24 lb. Paper

By Jay

Series: Leadership

Tags: leadership, education, organizational-behavior, reflection

And for most of the program, that’s exactly what I got.

But then came the capstone.

A Promise of Rigor

I don’t think it was too much of a stretch to expect the capstone to be a culminating experience, a chance to apply everything I’d learned in a meaningful way. Isn’t that what capstones are for? A chance to synthesize knowledge, to demonstrate mastery, to explore a research question that matters?

In terms of research questions, I had one ready: how does empathy function in crisis leadership, particularly during large-scale emergencies like the COVID-19 pandemic or the Russo-Ukraine war?

Both the pandemic and the Russo-Ukraine war were unfolding in real time, and I was seeing how leaders navigated these unprecedented challenges. I wanted to explore how empathy played a role in their decision-making, how they balanced compassion with action, presence with performance. How they led with something deeper than just decisiveness.

Having family and friends who were first responders and care workers during the pandemic, as well as a personal connection to the Russo-Ukraine war, made this question even more relevant. I wanted to understand how leaders in those contexts were navigating crisis, and how empathy played a role there too.

This wasn’t just idle academic curiosity; it was applied relevance with a profound personal connection.

So I expected the capstone to be a framework for that kind of inquiry.

Instead, it turned out to be academic Mad Libs.

Format Over Thought

What I found wasn’t a flexible, open-ended opportunity to explore a meaningful topic. Instead, it was a highly prescribed, step-by-step process governed by templates, formatting requirements, and a remarkable level of detail about how the final paper should be printed. Literally.

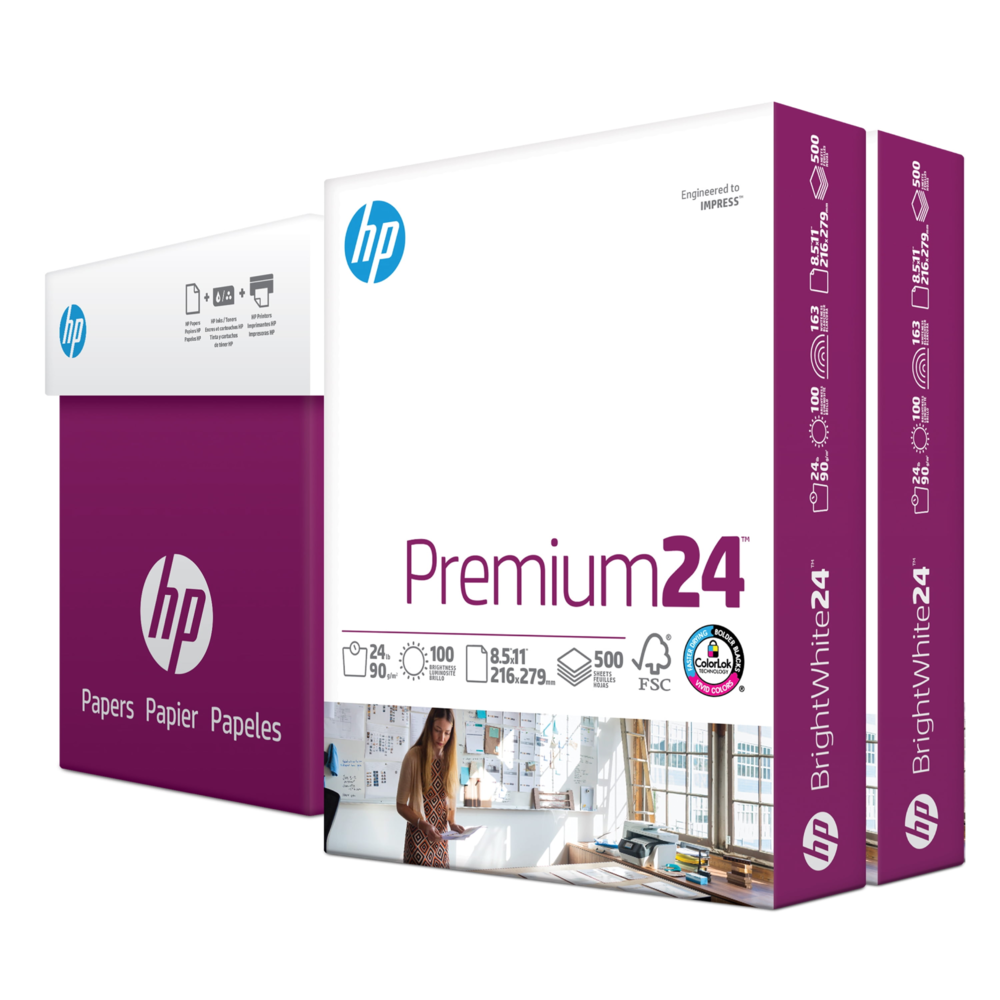

We were told what kind of paper to print on. Not metaphorically. Literally.

“Use white, 24 lb. paper,” the syllabus instructed, “so that you can be proud of your final product and display your hard work.”

This wasn’t a suggestion. It was emphasized alongside citation formatting and section labeling — not to mention guidance on binding. I couldn’t help but wonder who I was meant to be impressing: a future employer, or a bookshelf.

Of course, I never actually printed the paper. It was the middle of the pandemic, and everything was submitted electronically. Still, we were encouraged a number of times to print it. To display it and “show our hard work.”

The goal, it seemed, was not a strong argument or a novel insight — it was something that looks good.

And while that’s fine for a brochure, it’s frustrating for what’s supposed to be the intellectual culmination of a graduate program.

Talking Past Each Other

I didn’t get along particularly well with the instructor, and I’ll own part of that. It was a pandemic, we had two small kids, and I wasn’t exactly operating at peak patience. But even accounting for that, every conversation felt like it was happening in two dimensions: I was talking about ideas, while she was talking about indentation levels.

Her self-assuredness didn’t help. Nor did the tone of her feedback, which almost never engaged with the content of what I was writing and almost always focused on how closely it followed the prescribed structure. She was very confident in her approach — and that approach simply did not involve room for deviation, even when it might have made the work better.

Given this, the irony wasn’t lost on me that my capstone was about empathy, the very thing that was absent in our interactions. I was trying to explore how leaders could navigate complex human emotions in crisis, and my instructor was focused on her paint-by-numbers approach to a faux-academic exercise and could not see past the formatting.

It was, in a word, disillusioning.

The Cliff’s Edge

There were several points during the course when I seriously considered walking away. Not just from the class — from the program entirely.

And here’s the thing: that would have been consistent with my original goal. I didn’t enroll to get a degree. I enrolled to learn. Once that premise started to feel compromised — once it felt like the product mattered more than the process — quitting didn’t feel like failure. It felt like integrity.

What stopped me wasn’t some renewed faith in the process. It was the fact that I’d learned a lot in the courses leading up to the capstone. That learning still had value, even if the capstone didn’t reflect it. I stayed because the foundation was strong, even if the final chapter felt hollow.

So, I Did the Work

Despite the constraints, I did the work.

My paper — Leadership During Crisis: The Importance of Empathy — was based on interviews with three senior leaders across tech and academic organizations. I asked them how empathy influenced their decision-making, how they embedded human-first principles into their culture, and how they led in the most difficult moments.

One shared how layoffs tested his empathy:

“Knowing the personal impact of those decisions — a newborn at home, a visa in question — that becomes tricky when too much empathy risks unfairness to others.”

Another framed leadership as an act of humility:

“I’m not the smartest guy in the room… anything I can do to facilitate what they’re doing is a win-win.”

A third emphasized honesty and accountability over spin:

“People appreciate honesty more than attempts to sell them something… I’m certainly susceptible to being wrong, and the first finger I point will be at myself.”

Those interviews were the heart of my capstone. They were the substance that the format tried to obscure. They were the real-world insights that transcended the rigid structure I was forced to navigate.

They were the stories of leaders who understood that empathy isn’t just a nice-to-have; it’s a critical component of effective leadership, especially in times of crisis. They were tactical, reflective, and real. They revealed what the literature only hinted at: empathy, used well, improves communication, enhances performance, and fosters resilience. Yet it isn’t a panacea, as it has its limits, especially when under pressure, when leaders must balance individual care with organizational needs.

So, I wrote about all that, despite the constraints. I wrote about how empathy is not just a soft skill, but a strategic advantage in leadership. I wrote about how it can be the difference between a team that thrives and one that merely survives.

Style and Substance: A Leadership Problem Too

Like many things, some time and distance has given me perspective on the capstone experience. At the time, it felt like a frustrating exercise in compliance, a box to check rather than a meaningful exploration of leadership. But now I see it as a microcosm of a larger issue in leadership and education: the tension between style and substance.

From frustration, I’ve found clarity. The capstone was instructive. It showed me how easy it is — in academia, in business, in leadership — to confuse perception with reality.

The capstone was designed to look like a rigorous final project. It had all the trappings: structure, citations, deadlines, a submission protocol. It was polished, it was formatted, it was bound. It had all the right elements to make it appear like a serious piece of academic work.

Yet, in the end, it was just a template. It didn’t ask me to think deeply about my topic. It didn’t challenge me to explore the nuances of empathy in crisis leadership. It didn’t push me to engage with the complexities of human behavior and decision-making in times of uncertainty.

And that’s the core tension in leadership, too. We’re often rewarded for polish, not process. For managing perception instead of navigating reality. We’re told to follow the template, to hit the marks, to check the boxes. We’re encouraged to present a certain image, to adhere to a set of standards that prioritize form over function. Which works great, until it doesn’t.

When we focus on optics over substance, we risk losing sight of what really matters. We risk creating environments where compliance overshadows curiosity, where adherence to process trumps genuine engagement, and where the appearance of rigor replaces the pursuit of understanding.

And that takes us right back to the subject of my research. Empathy is the antidote to that. It’s the thing that reminds us to look past the frame and into the substance. To pause before pushing the template. To ask what someone needs, not just what’s required.

Coda

In the end, I finished the capstone. I printed it on the correct paper.

Just kidding — I didn’t print it at all.

But I did finish it. I turned it in. And I moved on.

What I actually took from the experience wasn’t in the binding — it was the insight that even well-structured systems can lose the thread. Even good programs can get tangled in their own optics. And even thoughtful educators can create environments where compliance overshadows curiosity.

What saved it, for me, was the work I did despite that.

And maybe that’s a leadership lesson, too.