Blog

Breaking Down Silos

By Jay

Series: Leadership

Tags: leadership, communication, systems-thinking, frameworks

“Communication is key.”

We all say it. But how often do we actually mean it? And how often do we hide behind it?

Communication is the platitude of choice when we either don’t know the real issue, or when we want to avoid confronting the real issues. It’s become the default diagnosis for failure, and one that unfortunately is often uncritically accepted.

It’s also an easy way to punch down. Most of us know that when we hear this term it’s code for: “someone lower on the org chart should have spoken up sooner.”

It’s not that communication isn’t important. It is. But it’s not the only thing that matters, and it’s often not the root cause of failure.

In many cases, “communication” is an easy answer to avoid the hard conversations about culture, power dynamics, and systemic breakdowns. Which is understandable, because those conversations are uncomfortable.

But if we want to improve how we work together, we have to get comfortable with the uncomfortable. So let’s talk about what actually breaks communication, and what we can do about it.

Three Ways Communication Fails (and Why They Keep Happening)

1. Silos: When Expertise Becomes Isolation

Take Apollo 13. Not the explosion part, the filters.

In a situation that everyone who works in tech has seen played out a thousand times, the Apollo 13 mission faced a critical failure not because of a lack of intelligence, but because of a lack of communication between teams.

The Command Module and Lunar Module used different oxygen scrubber designs: square cartridges and round receptacles. Two separate engineering teams, working in parallel, never bothered to align on that tiny-but-critical detail. When CO₂ levels rose, the crew had to scramble to fit a square peg in a round hole, using duct tape, flight manuals, and the sheer willpower of ground control.

“In complex systems, isolation isn’t safety—it’s entropy. Apollo 13 didn’t fail because people weren’t smart—it failed because smart people weren’t talking.”

This wasn’t a one-off. It was a symptom of a larger problem: siloed teams. NASA had a history of compartmentalized expertise, where each team operated in its own bubble, often to the detriment of the mission. Decades later, after the Challenger and Columbia disasters NASA’s own culture audit revealed that siloing was deeply baked into their organizational DNA.

In modern teams, silos happen when backend doesn’t talk to frontend, ops doesn’t talk to dev, and product doesn’t talk to either. It’s not malicious. It’s inertia. But it creates the same risk: incompatibility at exactly the wrong moment.

2. Power Differentials: When Warnings Get Ignored

Before Columbia disintegrated in 2003, retired engineer Don Nelson spent years warning NASA that its culture was headed for disaster. He wrote memos. He made calls. He waved every red flag he could find.

Leadership didn’t listen.

Not because they lacked data, but because they didn’t respect where the data came from. Warnings from “retired guys” didn’t carry weight in the halls of authority, even when those warnings were tragically accurate. The Chicago Tribune covered his story in 2003. To be clear, this was after the Challenger disaster, after the Rogers Commission report, after the lessons learned from that disaster.

3. Deference: When Culture Silences Correction

In 1999, Korean Air Flight 8509 crashed just minutes after takeoff. The captain, misled by a faulty instrument, kept climbing at a dangerous angle. The copilot and flight engineer noticed something was wrong, the airplane was stalling, and the alarms were blaring. But they didn’t challenge the captain. They deferred to his authority, they never tried to force a correction, and the plane went down, killing the entire crew.

Why did the crew stay silent? Because of a deeply ingrained cultural norm that prioritized hierarchy over safety. In South Korean culture, deference to authority was so strong that even in life-or-death situations, subordinates hesitated to challenge their superiors. They would rather die than risk offending the captain.

The British investigation cited cockpit hierarchy as a core contributor to the crash. A captain made an error. The rest of the crew didn’t challenge it. The plane went down.

This isn’t just a Korean problem. It’s a global one. In many work cultures, especially in tech, we reward compliance over challenge. We value “getting it done” over “doing it right.” We praise the person who hits the deadline, even if it means ignoring the warning signs. At least until the postmortem, when we all say “we should have communicated better.”

The Aviation Industry’s Fix: Crew Resource Management

The aviation industry had every excuse to do nothing. Pilots were experienced. Training was rigorous. Crashes were (relatively) rare.

But the data told a different story: pilot error was the leading cause of fatal accidents. Not because pilots were bad, or poorly trained, or even because they were tired. They didn’t crash because they were incompetent, or because they didn’t know what to do. They crashed not because of a lack of skill, but because of a lack of communication.

It’s a pattern we see in every industry. A team has the expertise, but the structure prevents them from using it effectively. A junior engineer raises a concern, but the VP has a deadline. A nurse questions a doctor, but the hierarchy is too rigid.

The wake-up call for aviation came in 1978 with United Airlines Flight 173. The aircraft circled Portland for over an hour troubleshooting a landing gear issue. During that time, the flight engineer repeatedly raised concerns about low fuel. The captain acknowledged, then dismissed them. Eventually, the engines flamed out. The plane crashed into a densely populated area, yet through sheer luck, no one on the ground was killed. The crash claimed 10 lives, including all but one of the crew.

It wasn’t a technical failure. It was a communication breakdown rooted in cockpit hierarchy. A junior officer had a critical warning, but the captain’s authority silenced it. The crew’s training didn’t include the ability to challenge authority, even when lives were at stake.

That crash became the crucible for a new idea: that leadership alone wasn’t enough. What was needed was resource management, where resources included not just equipment, but people. With communication treated as a life-critical resource.

The lesson? In leadership, you don’t just manage people. You manage power dynamics. You create space for voices that might otherwise be silenced.

To create that space aviation created Crew Resource Management (CRM), a framework for building communication muscle where it’s most likely to atrophy: under pressure.

CRM isn’t a product. It’s not a tool. It’s a system of behaviors that can be trained—not just taught, but practiced and reinforced. It’s not a one-time workshop, but an ongoing commitment to how teams relate to each other. It’s about how people can be empowered to speak up, how they can be heard, and how they can be challenged in a way that’s constructive, not punitive and how they can be supported in making decisions under stress.

It’s built on a few core principles:

- Anyone can speak up.

- Everyone must listen.

- Clarity beats politeness.

- Questions aren’t insubordination.

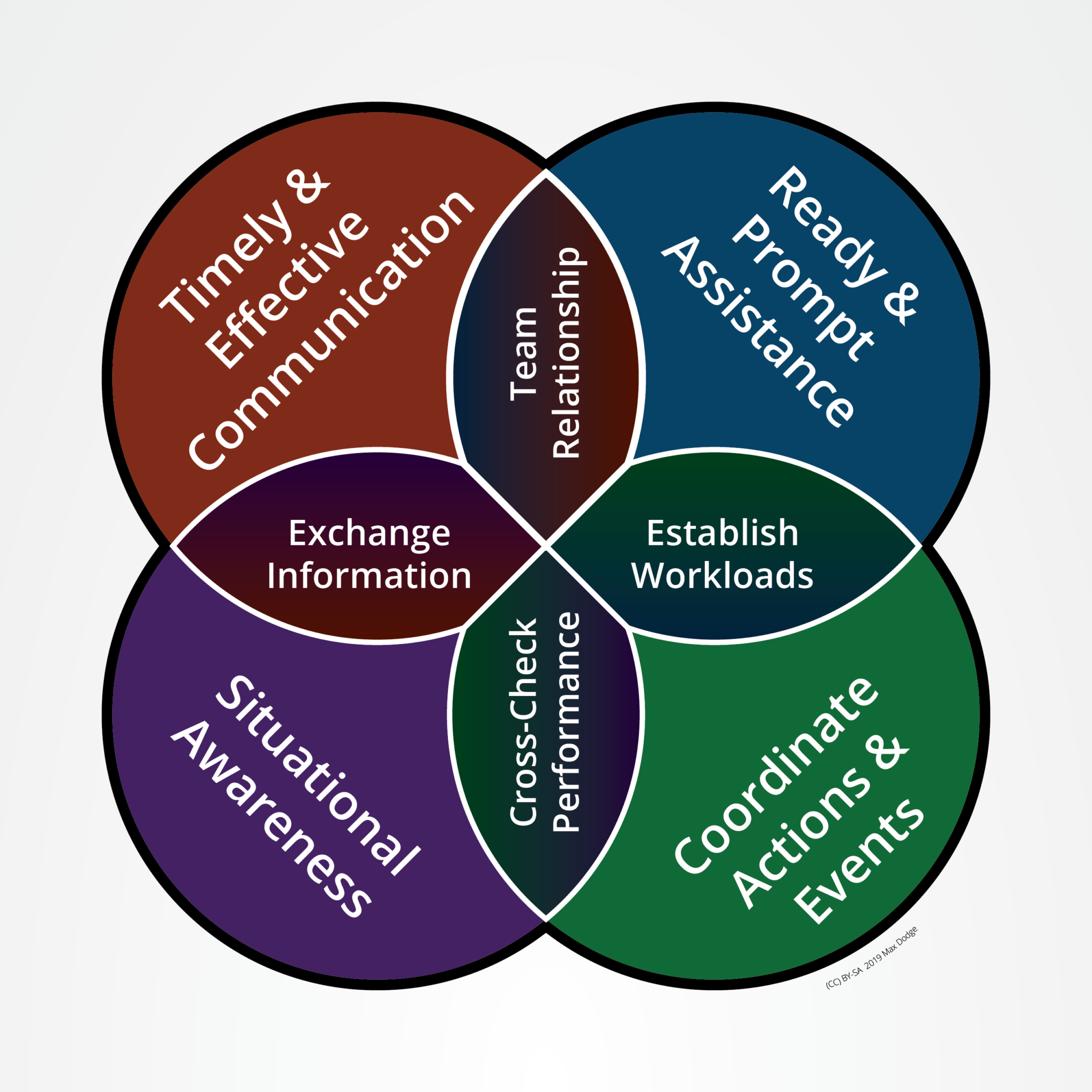

Source: Flight Safety Foundation — note how “Timely & Effective Communication” and “Coordinate Actions & Events” are central.

CRM made flying safer, not be adding more technology, but by redesigning how people relate to each other under stress. It worked. Airline accidents dropped sharply. Healthcare and nuclear energy adopted similar models. But in tech? We’re still saying “we need better communication.”

What This Means for Software Teams

You don’t need a cockpit to have a crisis.

Deadlines. Incidents. Misaligned teams. Slack messages that vanish into the void. All signs your org is communicating without connection.

So how do we adapt CRM?

- Start with culture. Build psychological safety before you need it.

- Blameless postmortems, pre-mortems, and retrospectives. Make them routine, not just after a failure.

- Encourage dissent. Make it safe to challenge decisions, especially from those lower on the org chart.

- Model challenge. If leaders don’t invite correction, no one will offer it.

- Name silos and power dynamics out loud. What’s visible is fixable.

From Reflection to Practice

To make this real, don’t just talk values. Build practices. Here are some CRM-inspired practices you can start today:

| Failure Pattern | Common Cause | CRM-Inspired Practice |

|---|---|---|

| Siloed delivery | Functional isolation | Cross-team design reviews |

| Ignored warnings | Authority bias | Pre-mortems with mandatory dissent |

| Quiet engineers | Psychological risk | Explicit “speak-up” norms in retros |

| Blame post-incident | Lack of safe feedback channels | Routine Morbidity and Mortality (M&M) style debriefs |

Historical Context Timeline

A brief look at how high-stakes communication failures shaped the development and adoption of Crew Resource Management (CRM):

1970 1978 1979 1981 1999 2003 2007+

| | | | | | |

| | | | | | +–> CRM expands into healthcare, nuclear energy, and tech

| | | | | +————> Columbia disaster reveals top-down culture at NASA

| | | | +———————> Korean Air 8509 crash exposes cultural deference

| | | +—————————–> CRM formally adopted in U.S. airline training programs

| | +–––––––––––––––––––> NASA workshop coins “Cockpit Resource Management”

| +———————————————–> United 173 crash: crew fails to communicate fuel emergency

+———————————————————> Apollo 13: oxygen scrubber mismatch reveals siloed engineering

Timeline Breakdown

| Year | Event | Link |

|---|---|---|

| 1970 | Apollo 13 oxygen scrubber mismatch exposes siloed teams | NASA Apollo 13 Overview |

| 1978 | United 173 runs out of fuel after ignored warnings—10 fatalities | NTSB Report AAR-79/07 |

| 1979 | NASA workshop coins “Cockpit Resource Management” | CRM Origins – NASA ASRS Report |

| 1981 | CRM formally adopted in U.S. airline training programs | NASA Ames CRM Training Guide |

| 1999 | Korean Air 8509 crashes due to cockpit deference | UK AAIB Report 2/2002 |

| 2003 | Columbia shuttle disaster reveals NASA power dynamics | Columbia Accident Investigation Board Report Vol. I |

| 2007+ | CRM adopted across healthcare, nuclear, and tech sectors | CRM in Medicine – PubMed Study |

Final Descent

Silos. Power gaps. Deference. These aren’t accidental. They’re engineered by the systems we build and the cultures we create. This creation may be passive, but it’s persistent. They’re not just technical failures, they’re human ones. And they persist not because we don’t know better, but because we allow them to.

CRM shows us that you can un-engineer them, too. It won’t happen through sentiment. It takes structure. Practice. Leadership that listens.

So yes, communication is key. But only if we change the locks.

Related Reading

- Systems Failures: The Quiet Collapse of Standards - How communication breakdowns lead to normalization of deviance

- Organizational Patterns: Systems and the Cobra Effect - When well-intentioned metrics create unintended communication barriers

- Leadership: From Line Cook to Chef - How experience gaps affect cross-functional communication

- Accountability: Leaders Who Fail Up - When communication failures get rebranded as leadership success