Blog

Drowning in Beeps

By Jay

Series: Leadership

Tags: systems-thinking, technical-management, observability, organizational-behavior

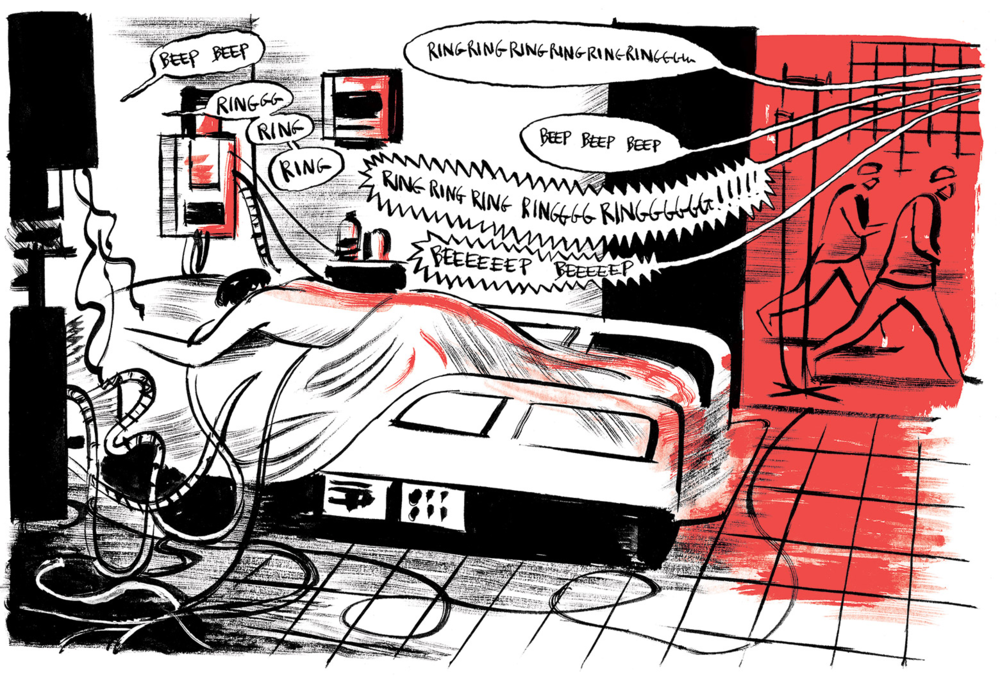

I’m writing this from the corner of a hospital ER, where I’ve been watching a wall-mounted monitor flash and beep on an endless cycle. IV pumps, telemetry monitors, access doors all have something to say, constantly. Harried nurses scurry through the ward, ignoring most of it, trying to stay ahead of whatever’s next. When I ask about the cacophony of alarms and beeps, they say: “Honestly, we just tune most of it out.”

The Cost of Listening to Everything

Alert fatigue is what happens when a system demands attention at such volume and frequency that the human brain learns not to care. It’s not just a problem, it a failure of design. The irony is that these alerts were built with safety in mind. In medicine, they’re meant to flag clinical deterioration early. In tech, they’re there to catch incidents before customers notice.

But if the alarms always go off. They go of for minor issues, non-issues, informational updates, and everything in between. The brain can’t keep up. It learns to ignore the noise, to filter out the static, to stop reacting. Unfortunately, learning to ignore the noise means learning to ignore everything.

At a previous job, I once inherited a system that was configured to send out pages for every single event, no matter how trivial. We would get a page when a backup started, when a backup finished, when a disk was 90% full, when a disk was 95% full, and so on. It was like being in a room with a toddler who had just discovered the siren button on their toy fire truck.

This was a classic case of alert fatigue. For 95% of the alerts, there was no action required. Of the remaining 5% nearly all were false positives. The small number that were actually actionable were lost in the noise. The team had become so desensitized that they’d stopped responding to alerts altogether. Worse, they’d stopped trusting the system.

Aviation Got Here First — and Taught Us How to Climb Out

This isn’t the first industry to face this problem. Aviation saw it decades ago. Planes got more complex, cockpits got noisier, and accidents happened not because crews weren’t paying attention — but because they were paying attention to the wrong thing.

Enter CRM: Crew Resource Management. A fancy name for a simple idea. People, not systems, are the last line of defense. And they need better support. CRM introduced structured communication, clear decision hierarchies, and a cultural shift where even a junior crew member could call out a safety issue without fear of retribution.

Tech eventually caught on. We’ve pulled some of those lessons into incident management, SRE handbooks, and even postmortems. Medicine’s adopted it too, in the form of team-based checklists and protocols. But we still haven’t fully learned CRM’s deeper lesson: If you want people to catch the right signal, you have to design for human attention, which means designing for trust, not just machine logic.

UI Matters More Than You Think

In both tech and medicine, UI design often gets treated like an afterthought and is frequently relegated to a “nice to have.” It’s seen as something that can be added later, or as a layer of polish on top of the “real” system. But UI is not just colors and buttons and fonts. It’s the interface through which humans interact with the system. Sure seems like a “real” part of the system to me.

When we think about alerting systems, we often focus on the backend: the telemetry, the thresholds, the logic that decides when to send an alert. All of which is important, but in conjunction with that we also need to consider what the human sees and what you expect them to do with that alert. That’s where the UI comes in.

To paraphrase Jeff Goldblum in Jurassic Park: “You were so preoccupied with all the things you could alert on, you didn’t stop to think if you should alert on them.”

Think about it. You can have perfect telemetry, but if you blast all that data out via your alert channel without any context, you’re just creating noise. If every alert looks the same, if every alert demands immediate attention, then nothing stands out.

Bad UI doesn’t just slow us down. Instead, it trains us to disengage. It teaches us that nothing is urgent because everything looks urgent. That’s how critical information dies: not in silence, but in noise.

Design for Trust, Not Control

Too many alerting systems are built on the assumption that the user is inattentive or irresponsible. Which leads to a design philosophy of paranoia: assume the worst, alert for everything, and never trust the user to make the right call.

But what if we built for trust instead?

What if we assumed that people do care, and will respond if we give them signal instead of static?

That shift — from designing for paranoia to designing for trust — changes everything. It means fewer alerts, better context, and more focus on actionable information. It means grouping related alerts, setting thresholds that matter, and using escalation logic to avoid overwhelming the user.

This means including the end user. The pilot, the sysadmin, the nurse, or whoever is on the other end of the alert. Ask them what they need. What helps them make decisions? What information do they trust? And importantly, what can they ignore?

The Prescription

We already know what to do. The patterns exist. We just need to apply them: • Alert Budgets: Set a max number of alerts per service, per week. If you hit the cap, tune the system. • Escalation Logic: Don’t treat every event as a fire. Use thresholds, timers, and grouping. • UI Layering: Design alerts like traffic lights — green, yellow, red — not like 100 sirens going off at once. • Postmortems for Alerts: If a team got woken up and it wasn’t urgent, figure out why — and fix it.

And above all, measure trust. The goal isn’t zero alerts. It’s alerts that people believe in. Alerts that they know matter. Alerts that they will respond to because they trust the system, not because they fear it.

Closing the Loop

Whether you’re running a datacenter or a trauma bay, the story is the same: when everything is an alert, nothing is. And when nothing stands out, it’s the human — the pilot, the engineer, the nurse — who ends up carrying the risk.

We can’t eliminate alarms, but we can make them meaningful. We can design systems that speak softly, clearly, and only when it counts.

Because the real danger isn’t the alert we missed. It’s the world we built that made us stop listening.